The progress of conservation in the US is paved by sportsmen, naturalists, philosophers, scientists, authors, activists and more. Despite their various, and sometimes clashing philosophies, their efforts added up to acre upon acre of preserved wilderness, and an ever growing awareness of our dependence on ecological integrity.

The progress of conservation in the US is paved by sportsmen, naturalists, philosophers, scientists, authors, activists and more. Despite their various, and sometimes clashing philosophies, their efforts added up to acre upon acre of preserved wilderness, and an ever growing awareness of our dependence on ecological integrity.

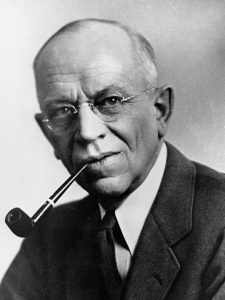

Even with so many players, it is doubtful that any single name is as revered among conservationists from all walks of life as the name Aldo Leopold.

Leopold began his career as a forester with the US Forest Service. By the end of his career, would produce hundreds of publications, launch conservation organizations, found the field (indeed, even the notion) of wildlife management , and hold the first such professorship at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

However, Aldo Leopold’s most influential contribution would emerge from the pages of an unassuming book of essays published posthumously. Through A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold would would awaken the minds and touch the hearts of readers for generations, and leave us with a work that would be deemed the cornerstone of the North American environmental movement.

Leopold was just the person to author such a book. He was the erudite professor lecturing with the brilliant prose of a poet. In ASCA, Leopold teaches us how to read and understand the land, and we learn that even the subtlest natural event may offer intuitive deduction and intriguing questions as we learn to see and wonder. To Leopold, “Every farm woodlot is a textbook on animal ecology; woodsmanship is the translation of the book.”

Part I of ASCA is a charming and thought-provoking trek through fields and forests, with Aldo as our guide. In January, we follow skunk tracks in the thawing snow, see what saplings the rabbits have girdled and draw thought-provoking deductions from hawks and meadow mice. In April, we watch the mating ritual of the woodcock’s Sky Dance. In June, we follow Leopold on a fishing trip on The Alder Fork, and sense that the value of the experience is in the pursuit. In October, we follow along with Aldo and his dog Gus through the Smokey Gold tamaracks of Adams County in pursuit of ruffed grouse. In November we take to the woods with Axe in Hand where we really begin to understand how the mind of a conservationist works. In December, we smile at Leopold’s enthusiasm for tracking chickadees.

Part I of ASCA is a charming and thought-provoking trek through fields and forests, with Aldo as our guide. In January, we follow skunk tracks in the thawing snow, see what saplings the rabbits have girdled and draw thought-provoking deductions from hawks and meadow mice. In April, we watch the mating ritual of the woodcock’s Sky Dance. In June, we follow Leopold on a fishing trip on The Alder Fork, and sense that the value of the experience is in the pursuit. In October, we follow along with Aldo and his dog Gus through the Smokey Gold tamaracks of Adams County in pursuit of ruffed grouse. In November we take to the woods with Axe in Hand where we really begin to understand how the mind of a conservationist works. In December, we smile at Leopold’s enthusiasm for tracking chickadees.

In the sections following the Almanac , Leopold’s prose becomes slightly more poignant as he wrestles head-on with some heavier issues such as predator control, the cultural value of wilderness, the role of science in conservation, and more.

Finally, in what is likely his most famous work, Leopold pulls it all together in brilliant fashion with the book’s capstone essay called The Land Ethic – a beautifully written exposition on the relationship between land and people.

“That land is a community”, Leopold explains in the Forward to ASCA, “is the basic concept of ecology, but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics. That land yields a cultural harvest is a fact long known, but latterly often forgotten.” It is those three concepts that Leopold so eloquently weaves together throughout his monumental book.

basic concept of ecology, but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics. That land yields a cultural harvest is a fact long known, but latterly often forgotten.” It is those three concepts that Leopold so eloquently weaves together throughout his monumental book.

In the end, we have an inspiring glimpse into the mind of one of history’s greatest conservationists. Most of all, however, Aldo Leopold left us with a piece of work that lays out the value of nature and a resounding call to preserve it, both for its own sake, and for ours.

For more on Aldo Leopold and his conservation legacy, or to purchase a copy of A Sand County Almanac, visit aldoleopold.org

Hunter S. Bridges